|

|

|

|

Is artistic ability a uniquely H. sapiens trait or was it shared with our former contemporaries as a form of self-expression,

religion, communication, or magic? Science may never be able to answer any questions of meaning, but we can still hope to

reach a consensus on the presence or absence of art created by our human cousins, Homo neanderthalensis.

|

|

|

| The myth about Neanderthals |

|

In order to answer questions about symbolism, one must expectedly determine the presence and extent of language usage.

Stephanie Johnson has offered proof that Neanderthals were capable of speech almost as complex as that spoken by modern humans.

The ability to speak goes far beyond communication; it entails perception, the ability to distinguish between past, present,

and future, and most importantly, the capacity to equate symbols with concrete concepts. With the relationship of language

and symbolism in mind, allow me to begin with a passage by William Noble and Iain Davidson (1991):

"Language is important in hunting ... because the planning that makes human hunting possible

(where hunting is distinguished from opportunistic predation) can only be realized linguistically. Planning for hunting is

a form of propositional thnking, and such thinking cannot occur in the absence of language. Nor can there be aesthetics in

hominids, where this is taken to refer to 'artistry' or 'taste,' unless the hominids had language, since aesthetics so conceived

is purely constituted by the cultural values that language alone can define. Language, in short, underpins all modern human

behavior. A search for the origins of one is a search for the origins of the other."

Introduction to the Neanderthals

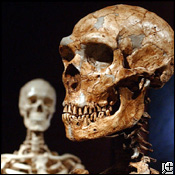

Homo neanderthalensis was first discovered in Neander Valley in Germany in 1856. Ever since the fossil human was found,

scholars have debated how closely modern humans are related to Neanderthals, be it genetically, behaviorally, or merely spacially.

To the general public, "Neanderthal" probably still incites images of a dim-witted, brutish Marcellin Boule-type creature

(Foley and Lewin, 2004), but to many scientists, anthropologists, and archaeologists, Neanderthals are far more similar to

modern humans than they are to our small-brained ancestors. Neanderthals had larger brains than modern humans, and although

evidence of their behavior is scarce, they may very well have had a thriving culture washed away forever only by a twist of

fate.

| Our Big-Brained Cousins |

|

The Discovery Channel presents a theory of Neanderthal extinction

History of a Species Time Left Behind

At about 127,000 years ago, classic Neanderthal traits began emerging. Neanderthal specimens have been discovered in many

parts of Europe and possess a myriad of cold-climate adaptations (Foley & Lewin 2004).

Neanderthals were short-statured, stocky creatures. Having relatively short limbs allowed the retention of more body heat,

enabling the species to endure colder temperatures than their Homo counterparts. They also boasted barrel-shaped rib cages

and large noses (Hoffecker 2002). These adaptations are thought to be useful in warming large amounts of air, which was very

cold and dry in Late Pleistocene Europe. These post-cranial traits are very important in the identification of Neanderthal

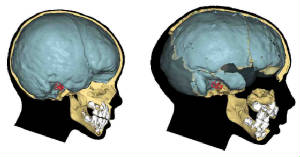

specimens, but one cranial characteristic is especially important in implications of intelligence, culture, and the capacity

for creativity. Neanderthals possess an occipital bun, a bony projecting feature on the back of their skulls. This feature

may have been necessary to accommodate their increasing brain size.

Neanderthals have a cranial capacity ranging on average "slightly over 1500 cubic centimeters" (Hoffecker, 2002). But is

a large brain all that is necessary to prove Neanderthals were creative beings? Probably not, but several rare artifacts may

shed light on Neanderthal behavior.

Discoveries

La Roche-Cotard

|

|

| Map of La Roche-Cotard in France |

In the early 1900s, the cave of La Roche-Cotard was discovered, but it wasn't until 1975

that extensive excavations began. The seventh level to be unearthed yielded artifacts of the Mousterian period,

which most likely belonged to the resident Neanderthals who lived there 30,000 years ago. It was also in this layer that Lorblanchet

and Marquet (2003) discovered what they have called a "proto-figurine," a mask-like stone that appears to have been created

by the Neanderthals of this site.

The proto-figurine is a large piece of flint that is "trapezoidal" (Lorblanchet and Marquet, 2003)

in shape. When looking at the flint from the mask side, the face is wider at the top than it is at the bottom. In the middle

of mask is a "natural tubular perforation or tube on an axis that is more or less parallel to the top and bottom edges of

the trapezoid" (Lorblanchet and Marquet, 2003). This can be thought of as the nose. Through this perforation, a bone splinter

has been forced and then secured. The splinter forms the eyes of the proto-figurine.

The physical aspects of the mask that imply Neanderthal alteration are the way in which

the bone splinter was secured through the perforation and the obvious evidence of percussion removal of flakes from the figure.

First of all, the bone splinter was secured almost perfectly evenly across the mask so that each "eye" is about the same size.

The manner by which the splinter was secured into the rocky bridge is also suspicious. "It is possible to affirm that the

splinter was purposely blocked inside thanks to two little flint plaquettes that were inserted ... between the splinter and

the block." There is also some beveling at the right end of the bridge, indicating the splinter was forced through the opening

(Lorblanchet and Marquet, 2003).

The second telltale sign of human alteration is the presence of percussion flaking scars. "Close

inspection shows that the object has been worked to give it a more regular shape." According to Lorblanchet and Marquet (2003),

there is clear evidence that the percussion method was used to remove flakes from the edges of the figure.

The BBC reports on the mask

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Arcy-sur-Cure

Archaeologists have also unearthed many artistic artifacts, mainly items of personal adornment, from the

Neanderthal levels of another French region called Arcy-Sur-Cure (Hublin and Spoor, 1996). The most prominent site within

this region for yields of Neanderthal pendants is the Grotte-du-Renne site (d'Errico and Joa, 2003). The question of whether

the Neanderthals of this site gained ivory discs, carved animal teeth, and other pendants from trade with anatomically modern

humans or by acculturation is still unanswered. The problem with the sites of Arcy-sur-Cure is that stratigraphic layers

are difficult to distinguish. There is some question of whether some Upper Paleolithic artifacts were mixed with Middle Paleolithic

layers over time, leading to a misinterpretation of the pendants.

Modern humans and Neanderthals at Arcy-sur-Cure

| Carved ivory tooth from Grotte du Renne |

|

|

| This tooth has a ring ground into the tip so a string or animal sinew can be tied around it. |

Explore the caves of Arcy-sur-Cure!

Because the stratigraphic layers of the Chatelperronian and Aurignacian have become muddled at the Grotte

du Renne site, it is difficult to accurately attribute artifacts to their makers. D'Errico and Zilhao (2003) argue that

there has been no stratigraphic mixing. They assert that the pendants and pierced teeth belong to Neanderthals because of

the unique technique by which they were fashioned. Anatomically modern humans made pendants by piercing holes through them.

The artifacts found in the Grotte du Renne did not have this feature. Instead, "Neanderthals carved a furrow around the tooth

root so that a string of some sort could be tied around it for suspension" (d'Errico and Zilhao, 2003).

According to d’Errico and Zilhao (2003), these items clearly cannot have belonged to modern humans because "finished

objects and the by-products of their manufacture" are found in the same stratigraphic levels, levels that represent a Neanderthal

period. Therefore, Neanderthals not only created pieces of jewelry; they even had their own unique technique for creating

it.

| Pendants from Arcy-sur-Cure |

|

| Stratigraphy is unclear. There is reasonable doubt as to who made these artifacts. |

Besides jewelry and sculpture, pigments used by anatomically modern humans have also been associated with

Neanderthal layers. "Black pigments, mostly manganese dioxides, and to a lesser extent fragments of ochre, come from at least

seventy layers excavated at forty Neandertal sites in Europe." (d'Errico, 2003) However, examples of use are rare so

it is therefore difficult to determine the significance of these pigments.

Foley, R. A. and Lewin, R. 2004. Principles of human evolution. United Kingdom: Blackwell Science Ltd.

Davidson, I. and Noble, W. 1991.

d'Errico, F. 2003. A multiple species model for the origin of behavioral modernity. Evolutionary Anthropology 12: 188-202

d'Errico, F. and Zilhao, J. 2003. A case for Neandertal culture. Scientific American 13:34-35.

Hoffecker, J. F. 2002. Desolate landscapes: Ice-age settlement in Eastern Europe. New Jersey: Rutgers University

Press.

Hublin, J. and Spoor, F. 1996. A late Neanderthal associated with Upper Palaeolithic artifacts. Nature 381:224.

Lorblanchet, M. and Marquet, J. 2003. A Neanderthal face? The proto-figurine from La Roche-Cotard, Lanqeais (Indre-et-Loire,

France). Antiquity 77:661-700.

Mellars, P. 1996. The Neanderthal legacy. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Created by Juliette Paradise

Maybe Neanderthals had music, too. Read about it!

| Check out this bone! |

|

| Could it be a Neanderthal flute? |

|

|

|

|